Ozempic Chic: Skeletal Is the New Black

(Apparently body positivity is taking an extended smoke break.)

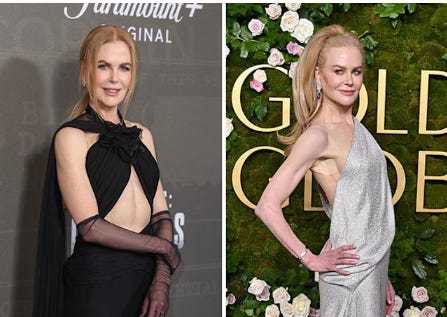

Scroll any red carpet, awards show, or press tour and you’ll notice it immediately: bodies are shrinking. Dramatically. Alarmingly. In record numbers. Even certain celebrities who spent the last decade preaching self-love, body acceptance, and the radical idea that women shouldn’t beat themselves up for not measuring up to some impossible beauty standard are suddenly sporting collarbones sharp enough to slice cheese.

We’ve been here before, of course. Even though we’re all pretty much stuck with the basic frames the good Lord gave us, the form-du-jour changes at least once a decade. Which means one minute, a naturally curvy girl can be the object of collective envy, and the next she’s starving herself to look like the human twigs gracing all the magazine covers and Met Gala photo spreads.

What’s amusing is that our actual personal preferences don’t shift all that much over time. People don’t wake up every few years craving a brand-new species of human. If you’re a dude who’s naturally attracted to slim, muscular women, no amount of “Sexy isn’t a size!” posters will override biology and turn Lizzo into your fantasy gal. Beauty ideals have never been driven by individual desire—they’re driven by culture, economics, technology, and massive marketing muscle.

Standards flip because industries need novelty to sell and status is signaled by rejecting whatever is accessible to the masses. When food is scarce, being well-fed suggests wealth. When food is abundant, thinness implies discipline, leisure, and control. When the middle class can get gym-ripped, too, the ideal migrates to something harder to achieve—hyper-curves, extreme thinness, or expensive pharmaceutical intervention. The body becomes a billboard, and the beauty barometer shifts to whatever look is just out of reach for 98% of the population.

The result is a rotating “ideal” that feels urgent and inevitable at the time… until it’s quietly replaced by the next one.

Let’s take a look at the bodies the past several decades decided were perfection without our input or consent:

1950s – Voluptuous / Hourglass

The boys were back from war, sex was on everyone’s mind, and womanly women—Marilyn Monroe, Sophia Loren, Jayne Mansfield—ruled the day. Busts and hips were celebrated, waists were tightly cinched (but certainly not rock-hard), and hunger was not considered a moral failure. Optimism was high and portions were generous. “Healthy” meant padded, ripe, and fertile—and nobody pretended it was about yoga.

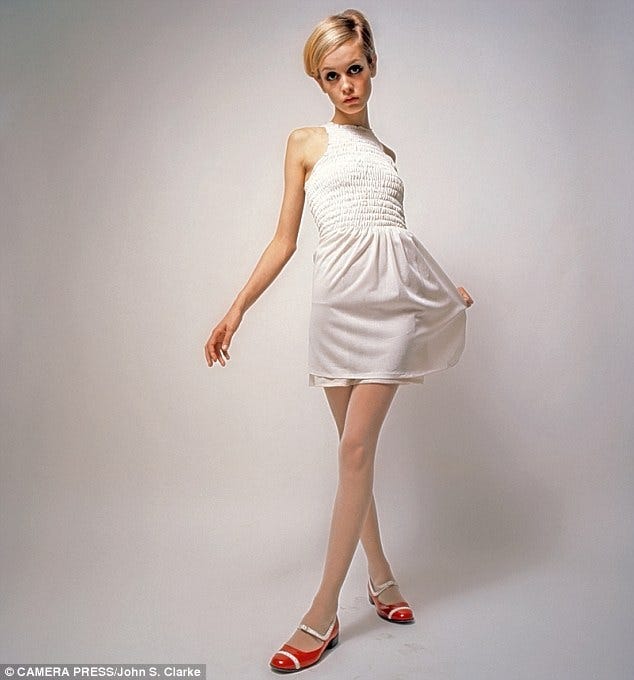

1960s – Waif / Skeletal

Twiggy almost singlehandedly detonated the curve economy. Structured, proper dresses made way for miniskirts and go-go boots—which just so happened to work best on a youthful, boyish, flat-chested body. Overnight, thin equaled chic—less “woman,” more “coat rack with eyeliner.”

1970s – Natural / Lean / Unstructured

Bodies were still thin, but less brittle. The look favored long, loose, earthy frames—Ali MacGraw, Farrah Fawcett, Iman. Boobs were optional, and fitness was not yet compulsory. This was hippie health, not starvation chic.

1980s – Fit / Toned / Athletic

Enter the Jane Fonda aerobics era. Strong thighs, visible muscle, and high-cut leotards defined the decade. Thin was still in—but this was thin you had worked for. The body became a project. Calories were counted, sweat was respected. You weren’t just skinny; you were disciplined.

1990s – Heroin Chic / Waif Redux

Kate Moss and Calvin Klein ads made looking malnourished a fashion goal. The aesthetic flipped to fragile, pale, and vaguely exhausted. Leg warmers were out; cigarettes and nihilism were all the rage. If you looked like you’d emotionally survived something and radiated peak “I don’t eat, I smoke” energy, you’d nailed it.

Early 2000s – Skinny but Sexy

Low-rise jeans terrorized a generation. Flat stomachs were mandatory, but now you also needed boobs—courtesy of push-up bras and implants. You had to be thin and hot (think Britney, Sarah Jessica, early Angelina) and hairless and somehow tan, while also avoiding the sun at all costs.

2010s – Extreme Kardashian Era

Gym culture collided with Photoshop and plastic surgery, edging the ideal into absurd, cartoonish curve territory. Natural bodies need not apply. “Thick” was everything, but only in exactly two places. Thinness never left; it just got redistributed.

Late 2010s – Body Positivity / All Bodies Are Beautiful

Social media exploded with plus-size models, empowerment campaigns, and “love the body you were born with” messaging. Taglines celebrated inclusivity and everyone applauded—before going back to secretly googling, “how to lose 10 pounds fast.”

2020s – Ozempic Chic / Thin Is Back (Again)

Almost without warning, everyone started downsizing. Jawlines jutted, ribcages protruded, toothpicks cosplayed as arms. Celebrities and regular folks alike insisted it was pandemic depression. Or Pilates. Or cutting out seed oils. Whatever the cause, skinny came roaring back, but this time with plausible deniability and a prescription price tag.

In earlier eras, extreme thinness required obvious effort—starvation, over-exercise, calling cigarettes ‘lunch’—so there was no denying the grind. Now, with Ozempic-style drugs, people can drop a dress size (or six) rapidly without admitting they intentionally pursued thinness, or that they wanted it at all. The new script isn’t “I’m dieting” or “I want to be skinny.” It’s “My doctor prescribed this for health reasons” or “I just lost my appetite.”

I know. We’re not supposed to comment on bodies—particularly women’s. Nobody owes the public an explanation for their weight, health, or medical decisions. Fine. Agreed. Gold stars for everyone.

But we are allowed to notice patterns. And the pattern right now is downright disturbing. What’s especially jarring is that this return to ultra-thinness comes after years of messaging that told women—particularly young ones—that they were finally free from impossible standards. Turns out the standards just took a lunch break. (They obviously didn’t eat.)

The names and (shockingly slim) faces are familiar: Lizzo. Oprah. Elon. Sharon Osbourne. Serena Williams. Kelly Clarkson. Chelsea Handler. Chrissy Teigen. Whoopi Goldberg. Amy Schumer. Jim Gaffigan. Many of the same celebrities who once positioned themselves as champions of authenticity now look like they’ve been folded in half and stored in a garment bag. “Ozempic body” is the new MD-sanctioned “heroin chic,” but with better lighting and a monthly invoice. Is it a medical miracle? For some people, maybe. Is it also a flex? Absolutely. Nothing says aspirational wellness like spending a thousand dollars a month to disappear more efficiently.

“Yeah, my momma, she told me, ‘Don’t worry about your size,’” a relatively round Meghan Trainor crooned in All About That Bass. “She says, boys like a little more booty to hold at night. You know I won’t be no stick-figure, silicone Barbie doll. So, if that’s what you’re into, then go ahead and move along.”

What’s different this time—and more troubling—is the speed. Weight loss that once took years of restriction, exercising, and quiet misery now happens on fast-forward. The cultural pivot didn’t creep in. It cannonballed.

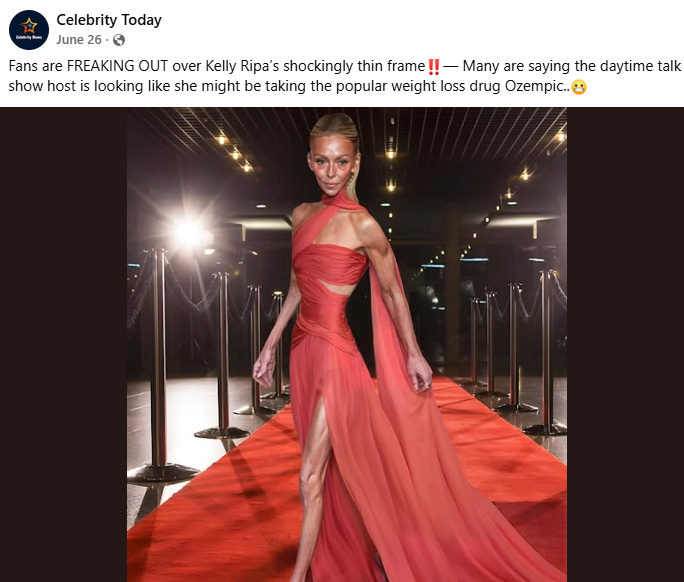

Equally unsettling is the extremeness. Because we’re not just talking about Adele suddenly looking like Kelly Ripa; we’re talking about Kelly Ripa suddenly looking like a Tim Burton character. Which makes even modestly-thin women (like me) wonder, “Did she think she was fat before? Does she think she looks good now? Am I supposed to think that looks good?”

I’m old enough to remember when the idea of having ribs removed was a far-fetched rumor linked to eccentric celebrities like Cher and Marilyn Manson. But now it’s an actual thing—being blamed on the “Ozempic body” trend and “rapidly gaining in popularity.” Of course, then there’s the pharma fallout: apparently the popular weight loss drug, which leaves people with sunken, droopy mugs, is also causing a spike in demand for early facelifts *where will it end?*

And while adults can make their own choices, the ripple effects don’t stop with them. Teen girls don’t distinguish between “medically supervised treatment” and “this is what pretty looks like now.” They just absorb. Compare. Internalize. Spiral. Repeat.

We’ve done this dance before, which is why the collective amnesia is so baffling. We know what happens when extreme thinness becomes the ideal. Eating disorders surge. Self-loathing skyrockets. “Concern” gets dismissed as jealousy or sanctimony. By the time everyone admits it went too far, the damage is already done.

Cue the apology tour.

Flesh goes in and out of style. Hemlines rise and fall. Eyebrows disappear and return. One generation worships curves; the next is obsessed with angles. Women’s bodies, for reasons known only to patriarchy and fashion executives, are treated like silhouettes on a mood board—adjustable, trend-responsive, and fair game for mass critique.

But add pharmaceutical acceleration to the mix, and suddenly it’s not just aesthetic whiplash. It’s cultural malpractice.

We’re told we can’t talk about the shriveling female form because it’s “dangerous.” It’s sexist. It’s stigmatizing. It’s degrading, dehumanizing, and dismissive. But pretending we don’t see what’s happening doesn’t make it any safer. Silence has never protected women from unrealistic expectations. It just lets them fester unnoticed.

Thin being back “in” wouldn’t be shocking on its own. What’s shocking is how fast we went from body positivity to body erasure, from “love yourself as you are” to “less is so much more,” from inclusivity to skeleton worship—in just a few short years.

Fashion cycles. Trends repeat. But biology and psychology don’t reset as easily. And when a culture once again starts rewarding women for shrinking—literally and figuratively—it’s worth asking whether we learned anything the last time around.

Big Pharma has found another way to keep humans chronically ill and make billions.

Read what Dr. Yoho says about Ozempic:

“The drug works by paralyzing the stomach, preventing proper digestion. This mechanism causes severe gastrointestinal problems in many patients. Nearly 3,000 lawsuits have been consolidated in the Pennsylvania federal court alleging gastroparesis, intestinal blockages, and ileus. The FDA has updated Ozempic’s warning label multiple times since 2023—adding warnings for ileus in September 2023, severe gastrointestinal reactions in January 2025, and pulmonary aspiration during anesthesia in November 2024.“

https://robertyoho.substack.com/p/396-ozempics-depravaties-make-the

Please tell me that photo of Kelly Ripa is doctored. It’s horrifying.

Back when I used to watch the idiot box (what my mother called the TV) I always wondered if Kelly had an eating disorder. If she looked that skeletal on TV, how did she look in person???!!!